The blog was started

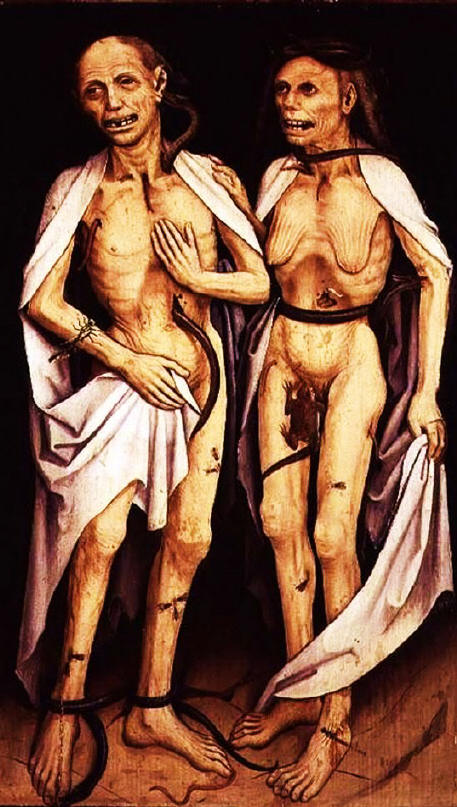

with the intention of answering the question, "how do the depictions of

death in illustrated manuscripts during the Black Plague reflect the attitudes

of the medieval society both socially and religiously?

A few of the problems I

ran into while researching this topic had to deal with finding reputable

sources. From my research, I had to rely on the use of non-scholarly sources,

as there just isn't much to be found that really goes in depth with

this topic. The scholarly sources that I found and used,

primarily dealt with more of the political and social aspects of society rather

than the true feelings of society. I figure this has a lot to do with the fact

that most of this history isn't written from the eyes of the average citizen

but rather from the clergy and other powerful figures which tend to leave sort

of a jaded version of it.

However, the sources that I did use did a damn good job at explaining the symbolism and meanings of what was depicted in the art. These symbols and their meanings helped draw connections to societal attitudes from politics to religion. I find these sources to more valuable in answering my original question.

For my conclusion, I have to be honest and say that I truly do not feel like I have a definite answer for my research question. I feel as if I have answered a portion of it, but to assess how it changed society is in my opinion nearly impossible. The lack of first-hand accounts from the people I want to hear from, the average citizen, makes this research one sided. I have read into many accounts from people representing the Church, but these two are biased and one sided.

Honestly, if I could go back to the beginning of the semester I would either change my research question altogether or at least modify it to be more researchable. As for my readers, like I said in my previous week’s post, if you have any questions, feel free to contact me at any time and I will try to answer them to the best of my ability.

However, the sources that I did use did a damn good job at explaining the symbolism and meanings of what was depicted in the art. These symbols and their meanings helped draw connections to societal attitudes from politics to religion. I find these sources to more valuable in answering my original question.

For my conclusion, I have to be honest and say that I truly do not feel like I have a definite answer for my research question. I feel as if I have answered a portion of it, but to assess how it changed society is in my opinion nearly impossible. The lack of first-hand accounts from the people I want to hear from, the average citizen, makes this research one sided. I have read into many accounts from people representing the Church, but these two are biased and one sided.

Honestly, if I could go back to the beginning of the semester I would either change my research question altogether or at least modify it to be more researchable. As for my readers, like I said in my previous week’s post, if you have any questions, feel free to contact me at any time and I will try to answer them to the best of my ability.